See also, Resources for Underprepared Students

Are Men the New At-Risk Population of Students?

Authored By: Terry Musser

2012

Introduction

It has come as somewhat of a shock to me that men on my campus are more likely to struggle with academic success than women. I have been tracking and supporting my students on probation for several years, and it concerns me that although only 45% of the students in my college are male, 68% of the students dropped for poor scholarship are male. The literature is flooded with research and implications for many at-risk populations, but the male cohort has only recently been recognized as one of these populations. This paper will explore the research related to why men are struggling and then offer some suggestions for working with our male students.

According to Harris (2010) et. al.:

- Majority of students cited for campus violations: male

- 90% of students accused of sexual assault : male

- Academic underachievement : male

- Disengaged in campus activities : male

- Most alcohol and substance abusers : male

It’s probably not a surprise that men are more likely to exhibit behaviors that are dangerous and potentially derailing for their academic careers. Boys will be boys, right? But the statistics are alarming and if we don’t do something to address this population on our campuses, we enable negative impacts on all of us.

We’re Losing Them!

In the 1980’s, 50% of the college population was male, but a mere twenty years later some reports place the total male enrollment in higher education in the United States at between 35 and 42 percent (Wimer & Levant, 2011; Harris, 2010). The largest gaps in male enrollment are with our most at-risk student populations. Of the African American students in college, 36% are male; of Native Americans, men represent 39% of that population; and 41% of all Hispanic students are male (KewalRamani, Gilbertson, Fox & Provasnik, 2007).

Studies conducted in the last decade show that males are struggling with socially constructed norms and what it means to be male (Wimer & Levant, 2011; Harris, 2010; Edwards & Jones, 2009; and Davis, 2002). Several studies have suggested that boys are expected to exhibit certain behaviors to maintain their masculinity and avoid being identified as “feminine” and these social pressures begin at a very young age. Parents, especially fathers, are known to support their boys in being tough, “take it like a man”, unemotional or emotionally disconnected, and engaged in masculine activities like sports. College-age men participating in these studies often claim they “perform” a certain way when they are among other males and some even termed this as “wearing a mask” that must not be removed around men at the risk of being considered feminine.

A Model of Male Identity Development

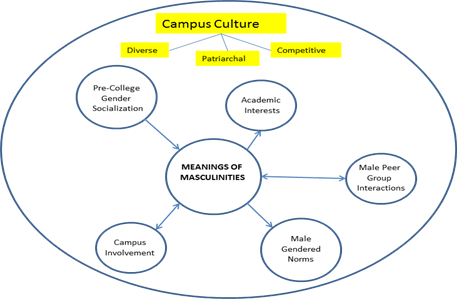

Studies of feminine development for several decades have produced models of identity development which can be used in our work with women. Research into male identity development has only been conducted in more recent years. Brannon (1985) formulated one of the earliest models known as the “Male Code” which includes four characteristics necessary for a male to be considered masculine: 1) the avoidance of acting in a feminine way; 2) striving to be recognized for successful achievement; 3) never show physical of emotional weakness; and 4) always be willing to engage in risky behavior, including participation in violence. Harris (2010) recently designed a model of male identity based on a study of male college students (see Figure 1.). The culture of the university campus surrounds and influences everything in this model. The campus culture has three characteristics that contribute to masculine identity: a diverse population of males; a patriarchal hierarchy among male students; and competitiveness among the male students. The diverse population of males allows for men to experience masculinity from other cultures and offers the opportunity to expand their meaning for male gender identification. The patriarchal nature of the student body tells men that fraternity members and student athletes are privileged and hold a higher social status on campus than those who do not belong to these groups. And finally male students are under constant pressure to compete with other men for status, attention and popularity. This culture was the primary reason for masculine behaviors reported by study participants such as drinking, working out and hooking up with multiple female partners for casual sex.

Figure 1.

Male students in the Harris study identified four major characteristics contributing to their meanings of masculinity: being respected, being confident and self-assured, assuming responsibility and embodying physical prowess. Specifically, being respected meant achieving admiration from other men and willing to stand up for oneself. Confidence and self-assuredness related to the student’s ability to behave the way they thought was right regardless of what others deemed appropriate for a male to do. Assuming responsibility had to do with preparing to become the bread winner or taking care of a family. And embodying physical prowess assumes that men who have large, muscular builds and displayed physical strength are more likely to attract women.

In this model, another contributing factor for male gender development is pre-college gender socialization. Various studies have examined the development of male identity in little boys. The early childhood development of males contributes significantly to the adult identity. Parents, especially fathers have a huge influence on little boys’ identification of what it means to be masculine. Playing sports, rough-housing and other activities are encouraged in the home while activities typically pursued by girls might be discouraged. The school system does not tolerate any sort of physical contact and discourages many of the typical male traits, causing a real disconnect with education and learning for boys. Achievement in physical activities is often valued more than academic achievement (Harris, 2010).

Male gendered norms represent the consequences or outcomes of pursuing a masculine identity. The “work hard-play hard” concept describes the ongoing challenge men face to balance intense academic expectations with the desire to engage in masculine activities like partying and hooking up with women. The abuse of alcohol, objectification of women, and pursuit of exclusively sexual relationships characterize hyper-masculine performance. Cultivating bonding relationships with male peers was a shared norm among participants in this study.

Interactions among male peer groups require specific behaviors and exclude certain behaviors as well. The main objective of these interactions is to not appear feminine. For example, groups of men in college often drink, smoke, cuss and talk sexually about women together. They actually talk differently about women than they do if women are present within the group. Talking about feelings or emotions would be considered feminine and would not be acceptable among peer groups.

Achievement and choice are two themes illustrated by academic interests. Academic achievement may not be accepted as a masculine trait in some circles but in many cultures it is. It’s important, therefore, for university personnel to NOT assume that the student is not motivated or is purposely not trying to succeed but may be feeling pressure from a peer group. Another interesting aspect of the masculine definition is the choice of a field of study. Because a man is still seen as the bread winner, male students are still choosing majors based on the future earning potential in that given profession. Certain majors would also be seen as traditionally masculine; for example, engineering, science, and business, while other majors are decidedly feminine like education, counseling, nursing, and communications.

Campus involvement also contributes to the development of meaning for masculinity. Males in the Harris study reported being involved in a variety of activities, some considered more masculine like sports, fraternities and student government; while others were involved in more gender-neutral activities like political science, student government, and ethnic student organizations. Leadership positions were common but primarily required to be at the highest possible level, like president or chair. Men identified the role of secretary or treasurer as being for women. Opportunities to interact with male leaders from other groups or organizations did allow the men in this study to expand their notion of masculinity by exposing them to men from other cultures with varying beliefs and norms of what it means to be a male.

Help-Seeking Behaviors in Men

It is already widely known that men are less likely than women to seek help for psychological, medical and career concerns (Addis & Mihalik, 2003; Blazina & Watkins, 1996; Rochlen & O’Brien, 2002; Wyke, Hunt, & Ford, 1998). Regarding academic help-seeking behaviors, Ryan et al. (1998) found boys to be more reluctant than girls to ask for help. So not only are we dealing with a student population that believes succeeding in academics is considered feminine by their male peer groups, but seeking academic help also carries the same stigma. In a study of 193 male undergraduate students at a medium-sized public university, Wimer and Levant (2011) found that male college students who conform to masculine norms are “highly unlikely to seek academic help when struggling in the classroom” (p. 266). The researchers propose that self-reliance and dominance are two masculine constructs that perhaps hinder men from seeking academic help. Their drive to be “stereotypically masculine” prevents them from accepting or admitting that they need help (p. 268).

What Can Advisors Do?

The studies referenced in this paper offer some suggestions for reaching out to our male students. The first step may be to identify which students are at risk early on and provide some intervention. Pollack (1999) suggests the following:

- Create a safe space for them

- Give them time to feel comfortable with expression

- Provide alternative pathways for expression

- Listen without judging

- Give affirmation and affection

These are suggestions that fit nicely into the world of academic advising. Some of the suggestions by Davis (p. 519) seem a little more clear and doable for advising professionals.

- Provide opportunities to reflect on masculinity

- Provide support by offering direct services to men (similar to programs offered to women)

- Male communication preferences:

- One-on-one

- With females

- Active, doing something

Fortunately, the communication preferences are something typically practiced in academic advising. The active, “doing something” type of communication means doing something active like taking a walk or completing an activity on the computer. This strategy could be adapted for academic advising appointments. Perhaps the best possibility for successful interventions would be for staff from the various student support programs on campus come together to discuss the issue of male students at risk and design support programs and services for them.

Harris (p. 315) offers an interesting intervention idea. He suggests that male peer groups from a variety of cultural backgrounds be given the opportunity to come together and discuss masculinity within their racial and ethnic cultures. This discussion could also include a goal setting activity for male students to be motivated to achieve in appropriate ways on campus.

Wimer & Levant (p. 270-271) offer the following suggestions to promote academic support seeking behaviors among men:

- Use masculine terminology for advising or counseling programs, i.e. “consultation” or “coaching”

- Emphasize skill development over personal growth or development

- Make advising centers more male friendly with décor and reading materials

- Provide integrated spaces for classes, study groups, faculty advising and student living (Living Learning Centers)

- Place advising centers near male dormitories

- Provide more online advising information and activities

Perhaps Edwards and Jones (p. 223-224) give us something we can begin to work on right away – achieve an understanding of male gender development and why our male students may be struggling. Here is what they have suggested:

- Understand partying for men as a trap to follow peer norms, not as resisting authority

- Create opportunities where men feel comfortable not “performing” but being their true selves

- Utilize advising, mentoring, or coaching relationships to connect directly with men and foster good interactions

- Give men permission to let go of partying and engage in academics and leadership

Conclusion

As academic advisors, we must not judge our students strictly by what is seen on a transcript or judicial affairs judgment. We must take time to treat every student as an individual who needs our attention and sometimes our affection and always our best efforts to understand and empathize with them. We must be more diligent in identifying all students at risk on campus and not exclude any group or population based on pre-conceived ideas about whether that group needs or will accept our help. This paper is by no means suggesting a lessening of support for our traditional at-risk populations. I am suggesting that we cast our net of support more broadly than perhaps we have in the past.

Terry Musser

DUS Programs Coordinator, College of Agricultural Sciences

The Pennsylvania State University

txm4@psu.edu

References

Addis, M.E., & Mahalik, J.R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help-seeking. American Psychologist, 58, 5-14.

Blazina, C., & Watkins, C.E. Jr. (1996). Masculine gender role conflict: Effects on college men’spsychological well-being, chemical substance usage, and attitudes toward help seeking. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 461-465.

Brannon, R. (1985). A scale for measuring attitudes about masculinity. In A. Sargent (Ed.), Beyond sex roles, p. 110-116. St. Paul: West.

Davis, T. L. (2002). Voice of gender role conflict: The social construction of college men’s identity. Journal of College Student Development, 43 (4), 508-521.

Edwards, K. E. & Jones, S. R. (2009). “Putting my man face on”: A grounded theory of college men’s gender identity developmnt. Journal of College Student Development,50, (2), 210-228. doi: ProQuest Education Journals

Harris, F. (2010). College men’s meanings of masculinities and contextual influences: Toward a conceptual model. Journal of College Student Development, 51, (3), 297 – 318. doi: ProQuest Education Journals

KewalRamani, A., Gilbertson, L., Fox, M., & Provasnik, S. (2007). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic minorities (NCES 2007-039). Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Pollack, W. S. (1999). Real boys: Rescuing our sons from the myths of boyhood. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

Rochlen, A.B., & O’Brien, K.M. (2002). Men’s reasons for and against seeking help for career-related concerns. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 11, 55-63.

Ryan, A.M., Gheen, M. H., & Midgley, C. (1998). Why do some students avoid asking for help? An examination of the interplay among students’ academic efficacy, teachers’ social-emotional role, and the classroom goal structure. Journal of educational psychology, 90, 522-535.

Wimer, D. J. & Levant, R. F. (2011). The relation of masculinity and help-seeking style with the academic help-seeking behavior of college men. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 19 (3), 256-274.

Wyke, S., Hunt, K., & Ford, G. (1998). Gender differences in consulting a general practitioner for common symptoms of minor illness. Social Science & Medicine, 46, 901-906.

Questions for Discussion

- Are men an at-risk population on your campus? How do you know?

- What can you do now to encourage male students to seek advising and take charge of their educational plans?

- What can you do to increase male students’ engagement in counseling and advising activities?

- How do you or can you identify male students at risk early in their academic career?

- What type of resources and/or support do you need to provide programming and interventions to recruit and retain male students on your campus?

- What other professionals do you need to partner with to address the issues for male students on your campus?

Cite this using APA style as:

Musser, T. (2012). Are men the new at-risk population of students? Retrieved from NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources Web site:

http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Males-as-an-at-risk-population.aspx